The rescued Nubian temples were moved and re-assembled in new locations: the temples of Philae on the island of Agilika, near the old Aswan Dam ; the temples of Beit al-Wali, Kalabsha and the kiosk of Qertassi a few hundred meters south of the High Dam; the temples of Wadi El-Sebuâ, Dakka and Maharraqa, 140 km south of the High Dam; the temples of Amada, Derr and the tomb of Pennut, 180 km from the High Dam ; and the two temples of Abu Simbel, 270 km from the High Dam. Four Nubian temples were offered to countries that had provided significant assistance in the salvage operation: the temple of El-Lessiya to Italy; that of Debod to Spain the temple of Taffa to the Netherlands; and the temple of Dendur to the United States. Other monuments were offered to other participating countries such as France, Poland, Germany, etc.

Several schemes had been presented to save the temples of Abu Simbel The one which was selected in 1963 had been submitted by a Swedish company called VBB. The work cost nearly 40 million USD. It took one year (August 1965 - July 1966) to cut the two temples into 1042 enormous blocks weighing over 15000 tons. The blocks were then re-assembled around a concrete superstructure, surrounded by a dome to mimic the topography on which the temple was originally located, over 200 m north and 65 m above its original location. The new site was inaugurated on September 22, 1968, but work on the final elements lasted until 1972.

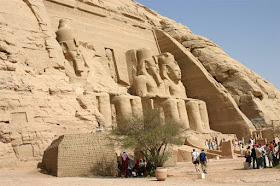

The Great Temple of Abu Simbel was completely carved out of the rock. Its facade, trapezoidal in form to mimic the pylon, is preceded by a terrace decorated with a series of upright statues of Horus and Ramses II. The facade is adorned with four colossal statues carved into the rock representing Ramses II seated and looking eastward. Around the king’s legs are statues of queens, princesses and princes. The facade is dominated by a row of baboons greeting the rising sun. Above the entrance is a niche containing a statue of hawk-headed god Ra-Horakhty. The entrance leads to a large hall, the ceiling of which rests on two rows of four Osirian pillars. In this hall, the reliefs are exceptionally well preserved. The eastern reliefs represent two nerely symmetric scenes of the Pharaoh smiting his enemies. On the northern wall, one can admire a detailed composition of the famous Battle of Qadesh, in which Ramses II confronted the Hittites in the fifth year of his reign. As for the scenes of the southern wall, they show, from left to right, the king on his chariot attacking an Asian fortress, killing a Libyan enemy, and, finally, triumphant, atop his chariot. Off of the grand hall are a series of rooms called « treasure rooms». Most likely, it was here that the most precious articles of the temple had been stored. The back door of the hall leads to a room with four pillars. The north and south walls of this room are decorated with scenes of worship of the divine boats. It then leads to a rectangular vestibule containing three sanctuaries. In the middle one, four statues are carved into the rock representing, from left to right, Ptah, Amon-Ra, Ramses II and Ra-Horakhty. As Amelia Edwards, who visited the site in 1874, noticed for the first time, the three statues on the right are completely illuminated by rays of the sun from the entrance of the temple on October 21 and February 21 every year (Currntly on October 22 and February 22).

The small temple of Abu Simbel is located 150 m to the north of the Great Temple. Its facade, 12 meters high, is decorated with six colossi, each reaching nerely 10 meters high: four represent Ramses II and two represent his royal wife, Nefertari, to whom the temple is dedicated. Statues of the royal couple’s children are carved on both sides of their legs : the princes on the king’s side, and the princesses on the queen’s. The entrance leads to a hall with six Hathorian pillars. Its walls are adorned with scenes of offerings and worship to the deities honored in the temple. To the west of the hall are three doors leading to a vestibule from which the sanctuary is accessed. The latter is decorated on the back wall with a sculpture of the cow goddess Hathor protecting Ramses II.

The temples of Abu Simbel were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1979, and they enjoy special treatment in terms of conservation and preservation. You too can help us to protect these two prestigious historical monuments by respecting these guidelines.

Stages of the transfer of Abu Simbel Temples:

Several schemes had been presented to save the temples of Abu Simbel The one which was selected in 1963 had been submitted by a Swedish company called VBB. The work cost nearly 40 million USD. It took one year (August 1965 - July 1966) to cut the two temples into 1042 enormous blocks weighing over 15000 tons. The blocks were then re-assembled around a concrete superstructure, surrounded by a dome to mimic the topography on which the temple was originally located, over 200 m north and 65 m above its original location. The new site was inaugurated on September 22, 1968, but work on the final elements lasted until 1972.

The Great Temple of Abu Simbel was completely carved out of the rock. Its facade, trapezoidal in form to mimic the pylon, is preceded by a terrace decorated with a series of upright statues of Horus and Ramses II. The facade is adorned with four colossal statues carved into the rock representing Ramses II seated and looking eastward. Around the king’s legs are statues of queens, princesses and princes. The facade is dominated by a row of baboons greeting the rising sun. Above the entrance is a niche containing a statue of hawk-headed god Ra-Horakhty. The entrance leads to a large hall, the ceiling of which rests on two rows of four Osirian pillars. In this hall, the reliefs are exceptionally well preserved. The eastern reliefs represent two nerely symmetric scenes of the Pharaoh smiting his enemies. On the northern wall, one can admire a detailed composition of the famous Battle of Qadesh, in which Ramses II confronted the Hittites in the fifth year of his reign. As for the scenes of the southern wall, they show, from left to right, the king on his chariot attacking an Asian fortress, killing a Libyan enemy, and, finally, triumphant, atop his chariot. Off of the grand hall are a series of rooms called « treasure rooms». Most likely, it was here that the most precious articles of the temple had been stored. The back door of the hall leads to a room with four pillars. The north and south walls of this room are decorated with scenes of worship of the divine boats. It then leads to a rectangular vestibule containing three sanctuaries. In the middle one, four statues are carved into the rock representing, from left to right, Ptah, Amon-Ra, Ramses II and Ra-Horakhty. As Amelia Edwards, who visited the site in 1874, noticed for the first time, the three statues on the right are completely illuminated by rays of the sun from the entrance of the temple on October 21 and February 21 every year (Currntly on October 22 and February 22).

The small temple of Abu Simbel is located 150 m to the north of the Great Temple. Its facade, 12 meters high, is decorated with six colossi, each reaching nerely 10 meters high: four represent Ramses II and two represent his royal wife, Nefertari, to whom the temple is dedicated. Statues of the royal couple’s children are carved on both sides of their legs : the princes on the king’s side, and the princesses on the queen’s. The entrance leads to a hall with six Hathorian pillars. Its walls are adorned with scenes of offerings and worship to the deities honored in the temple. To the west of the hall are three doors leading to a vestibule from which the sanctuary is accessed. The latter is decorated on the back wall with a sculpture of the cow goddess Hathor protecting Ramses II.

The temples of Abu Simbel were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1979, and they enjoy special treatment in terms of conservation and preservation. You too can help us to protect these two prestigious historical monuments by respecting these guidelines.

Stages of the transfer of Abu Simbel Temples:

View from the Nile of the Small Temple on its original site (old site)

In November, 1964, a steel culvert through the sandfill in front of the Great Temple waserected, to form an access to the temple rooms

Dismant'ing of the Hypostyle Hall (Great Temple)

The originial site after the process of cutting the temple' stones

-Using saws in the cutting process

Queen Nefertari as now temporarilyosened from her place at the leg of her royal consort

The statue of Ramses the Great

Pharaoh's knees being lifted after being cut loose

In February 1966 the dismantling of the temples was not far from completion

On arrival at the Storage Area, every block is carefully lifted by a gantry crane and moved to its provisional place while awaiting re-erection

Pharaoh regains his face

Behind the re-erected statues of King Ramesse the first arch element of the great dome above the temple rooms is under construction

Sky view of the Great Temple

The two Abu Simbel temples as they can now be seen from Lake Nasser on their new sites

When approaching the Great Temple, the visitor feels almost overwhelmed by its beauty and grandeur