The Pharaoh Senusret III was one of the most emblematic monarchs in Ancient Egypt. At the peak of the Middle Kingdom, his reign (circa 1872-1854 B.C.) marked a turning-point in the history of Ancient Egypt. This strategist and visionary sovereign conquered Nubia (now the Sudan) where he had a network of fortresses built; set the first boundaries of his kingdom and established trade and strong diplomatic relations with his eastern neighbors (now Cyprus, Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, Israel and the Palestinian Territories). His military expeditions and the setup of a loyal administration meant he could consolidate his power. The Egyptian state was restructured in depth.

These changes were embodied in statuary art: the surviving enigmatic portraits of the Pharaoh show a break with tradition, depicting either stern features, symbolic of wisdom, or an idealized young man. Other artistic output (jewels, objects of everyday life, burial equipment) illustrates regained prosperity and obviously vigorous cultural exchanges with neighboring kingdoms. The public will discover the artistic riches of a key reign, considered to be a golden age of Ancient Egypt.

If this pharaoh doesn't have the fame of Tutankhamen or Ramses II, he is, in the eyes of historians and archaeologists, the pharaoh who in the beginning of the second millennium BC made Egypt into a powerful state, and who remained a model for his successors. Many striking examples of the numerous representations of Senusret III, for the most part statues but also low reliefs, are shown in the exhibition. They reveal the authoritarian, inflexible character of the ruler who could also be merciful and attentive to his people. Providing Egypt with a restructured administration that led to a new social order, he extended the limits of his empire towards the north and the south, leaving traces of his conquests on these territories.

Sculptures of Sensuret III:

Senusret III is known for his strikingly somber sculptures. Senusret III is considered to be perhaps the most powerful Egyptian ruler of the dynasty, and led the kingdom to an era of peace and prosperity. Senusret III is known for his strikingly somber sculptures in which he appears careworn and grave.

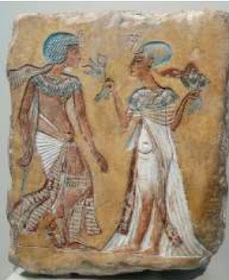

While many statues portray him as a vigorous young man, others deviate from this standard and illustrate him as mature and aging. This is often interpreted as a portrayal of the burden of power and kingship. Another important innovation in sculpture during the Middle Kingdom was the block statue, which consisted of a man squatting with his knees drawn up to his chest.

During the Middle Kingdom, relief and portrait sculpture captured subtle, individual details that reached new heights of technical perfection. Some of the finest examples of sculpture during this time was at the height of the empire under Pharaoh Senusret III.

Khakhaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or Sesostris III) ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC, and was the fifth monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. His military campaigns gave rise to an era of peace and economic prosperity that not only reduced the power of regional rulers, but also led to a revival in craft work, trade, and urban development in the Egyptian kingdom. One of the few kings who were deified and honored with a cult during their own lifetime, he is considered to be perhaps the most powerful Egyptian ruler of the dynasty.

Aside from his accomplishments in architecture and war, Senusret III is known for his strikingly somber sculptures in which he appears careworn and grave. Deviating from the standard way of representing kings, Senusret III and his successor Amenemhat III had themselves portrayed as mature, aging men. This is often interpreted as a portrayal of the burden of power and kingship. That the change in representation was indeed ideological and should not be interpreted as the portrayal of an aging king is shown by the fact that in one single relief, Senusret III was represented as a vigorous young man, following the centuries old tradition, and as a mature aging king.