In 529 BCE, the Greek general of mercenaries, Phanes of Halicarnassus, betrayed the Egyptian pharaoh Amasis (r. 570-526 BCE). Thus the Persian king Cambyses II was able to threaten the Egyptian frontier. After Amasis died, his successor,

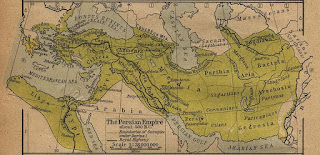

Psamtik III, was conquered and captured bv Cambvses in the battle of Pelusium (525 BCE). Egypt then became, with Cyprus and Phoenicia, the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. With Cambyses II, the First Persian Occupation began Egypt's twenty-seventh dynasty, and it includes Darius I (r. 521^486 BCE), Xerxes (r. 486-465 BCE), Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BCE),

Darius II (r. 423-405 BCE), and Artaxerxes II (405- 359 BCE). The Greek historian Herodotus traveled in Egypt about 450 BCE, so the Egypt he described was a Persian satrapy.

Memphis continued as the capital (as it had been under the previous Saite dynasty) and was soon the residence of the Persian satrap, who headed Egypt's entire administration. Various officials and numerous scribes were employed, and among these were Egyptian scribes for reports in their native language, while the official language became Aramaic. The garrison posts continued to be situated in Mareotis, Daphnis, and Elephantine, yet everywhere in

the Nile Valley, between the Delta and Nubia, there was a presence of Near Eastern foreigners, merchants, and soldiers— Phoenicians, lonians, and Car-ians—from all of the satrapies throughout the Achaemend Empire.

The First Persian Occupation began with Cambyses, who undertook an "Africa" policy, with three unsuccessful expeditions against Carthage on the Mediterranean, against the oasis of the Libyan Desert, and against Nubia. Cambyses assumed a pharaonic guise, as indicated by autobiographical texts of Wedjahorresenet, a high official and court doctor. The texts are engraved on his naophorus statue (now in the Vatican Museum), a basalt statute brought from Egypt and discovered at Tivoli in the ruins of Hadrian's villa. Wedjahorresenet served under Amasis, Cambyses, and Darius I. For Cambyses Wedjahorresenet created the epithet mswty-R" ("Born of Re"), Cambyses was interested in removing the "foreigners" (evidently members of the army of occupation) from the temple of Neith at Sais, to purify the temple, to return to the goddess her annuity, and to reestablish the priests, ceremonies, and processions as they had been before.

Ruin and oppression certainly could have occurred throughout Egypt during the violence of the conquest; but the evidence for the ferocity and impiety of Cambyses in Egypt, referred to by the Greek historians, is not supported by contemporary Egyptian documents. A stela from

the Serapeum (the underground catacombs where the

Apis bulls were buried at

Saqqara) dated from the sixth year of the Cambyses rule, testifies that Cambyses did not kill Apis, but that instead, the sacred bull, born in Year 27 of Amasis, received solemn obsequies and was buried in a sarcophagus donated by the same Cambyses, and that the succeeding Apis, born during the reign of Cambyses, died of natural causes in Year 4 of Darius I (as is shown by another stela from the Serapeum). To understand the foundation of the anti- Cambyses tradition, it is worth considering the resentment on the part of the Egyptian priesthood, which had been stung by Cambyses' decree that drastically limited royal subsidies to the Egyptian temples previously in effect.

The posthumous persecutions of Amasis by Persian conquerors is suggested by the Cambyses legend related by the Greek and Roman historians. In it, Cambyses, a grandson of Apries, took revenge against the usurper Amasis and reclaimed the throne of his grandfather. In 522 BCE, on the return trip home to Persia, Cambyses died from a leg infection incurred while in Syria. There, in the court circle of Susa, the rebellion broke out of the sorcerer Gaumata, claimant to the legitimate succession of Cyrus. The circumstances of the death (a dagger wound to the thigh that became gangrenous) are related by Herodotus as proof of divine punishment—since the wound was in the same spot that would have resulted from an attack on the Apis bull by Cambyses. According to Dio-dorus Siculus, Cambyses' death is punishment for his impiety. He is contrasted with the piety of his successor Darius I, who was generous toward the temples of the Egyptian gods and revoked Cambyses' decree.

Darius I (522-486 BCE) was the son of Istaspe, satrap of Hyrcania; Darius was a tolerant and strong ruler who restored order in the empire and conquered a new province, India. According to Diodorus, Darius I was the sixth and last law-giver of Egypt, as confirmed by the Demotic papyrus mentioned above. In his third year of rule, Darius ordered his satrap in Egypt to convene the learned among the soldiers, the priests, and the scribes so as to codify the laws in use to Year 44 of the reign of Amasis. His committee of wise men sat for sixteen years, until Darius's nineteenth year. Between his nineteenth and twenty-seventh year, the committee was reunited at Susa and the laws were transcribed on papyrus in Aramaic and Demotic. Such a juridical guide for Egypt was needed by the administration of that satrapy, since they were generally Persian or Babylonian and their official language was Aramaic.

The protection accorded to Egyptian temples and priests by Darius I was extended to the construction of a grand temple to

Amun-Re, in the Kharga Oasis (an archive of Persian-era Demotic ostraca was recently found at Deir Manawir). Darius Is building activities in Egypt are also known from the hieroglyphic inscriptions in the quarries of Wadi Hammamat, from blocks with Darius' cartouche found at Elkab, and from those at Busiris in the Delta. A large number of the

Saqqara Serapeum stelae have dates between the third and fourteenth year of Darius I. A small stela from the

Faiyum (now in the Berlin Museum) is dedicated to

Darius I in the form of the falcon-god HOI-US. The Vatican naophorus statue of Wed-jahon'esnet reveals that Darius ordered restoration work at the "House of Life" at Sais.

Yet rebellion against the Persians was constant. Aryandes, the first satrap of Egypt, was deposed by Darius I after rebelling. Pherendates succeeded him in 492 BCE and was the satrap to whom Peteese of Teudjoi referred his petition in Year 9 of Darius I, to obtain justice (Demotic Papyrus Rylands IX). To intensify contact with the Egyptian satrapy, Darius I accomplished an objective imagined but never carried out by Necho II—the opening of a navigable route from the Nile to the Red Sea. This was accomplished by means of a canal 45 meters wide and 5 meters deep (130 by 15 feet) that could be traveled for some 84 kilometers (52 miles), enabling navigation from Bubastis at Lake Timsah by the Bitter Lakes (Gulf of Heroonpolita) to the Red Sea in four days. Along the route of the canal were erected commemorative stelae of large dimensions—over 3 meters (10 feet) in height and 2 meters (6 feet) in width—in the three languages of the empire: Elamite, Akkadian, and Old Persian; they were located at Suez, at Chaluf or Kebret, at the Serapeum, and at Pithom (Tell el-Maskhuta). The waterway, which tended to silt up in the southern part, was put back into use under Ptolemy II (according to the stela discovered at Pithom) and also under the Roman emperor Hadrian. From as early as Cambyses, the Persian kings resorted to Egyptian sculptors and stonemasons, who are often mentioned on the Elamite foundation tablets of Persepolis. Many learned Egyptians, especially doctors, resided at the Court of Susa.

Trade with Persia was important to Egypt. An Aramaic text, recovered by B. Porten and A. Yardeni, contains the accounts of many colonies and of maritime traffic for a port (probably Memphis) during Year 11 of Xerxes I (475 BCE). The captains of the ships—which brought gold, silver, wine, oil, and lumber—are indicated as lonians and have Greek names (e.g., Simonides, Moskhos, Tymok-ledes, Mikkos, lokles, Phanes', etc.); other ships' captains are perhaps Phoenician. The boats returned loaded with Egyptian natron (sodium carbonate), highly valued in antiquity for the manufacture of glass.

From 404 to 343 BCE, the recovered independence of Egypt included the twenty-eighth, twenty-ninth, and thirtieth dynasties. The rulers of the thirtieth dynasty defended Egypt from Persia's attempts at reconquest, even resorting to alliances with the Greeks. Nektanebo I secured the support of the priesthood by a maneuver that consisted of a customs tax on merchandise that arrived at Naukratis in the Nile Delta (the Greek emporium from the time of the Saite kings), allotting 10 percent of the tax to the temple of Neith at Sais. Nektanebo's son Tachos (or Teos; r. 362-360 BCE) intervened militarily in an anti-Persian role in Syria, but his uncle, the general Tjaha-pimu, who was kept in Egypt as regent, took advantage by placing his own son, Nektanebo, by the Queen Udjashu, on the throne. This change was favored because of the discord incurred by the financial measures that Tachos took. He limited the priests' revenues and a tax was imposed on housing and on the grain to be offered to Atria, in addition to the tenth due on ships and crafts. Tachos, betrayed by the Spartan general Agesilaos, fled Egypt, took refuge at Sidon, and then at the Persian court at Susa.

Nektanebo II (r. 361/60-343 BCE) repelled two Persian invasions: one in 358 BCE, by the army of Prince Arta-xerxes; the second in 351 BCE, led by the same man, now Ar-taxerxes III Ochus. When he retook Cyprus and Sidon, he was able to land at Pelusium in the Nile Delta. From Pelu-sium, the Persians then took the other cities of the Delta and as far south as Memphis. Nektanebo II escaped to Nubia with his treasure. Classical sources accuse

Artaxerxes III of violence and brutality even more subtle than that ascribed to Cambyses. Then in 338 BCE, the eunuch Bagoas murdered Artaxerxes; in 336 BCE, he also killed the king's son and successor Xerxes. Under Darius III, the satrap Sabace fought and died at Issus. The last Persian satrap, Mazaces, lost Egypt to Alexander the Great of Macedon in 332 BCE. The Achaemenid Empire had ended, and Egypt had become a province once more. After Alexander, the Ptolemies and then the Romans became the masters of the Nile Valley, which was governed by foreign rulers until after World War II.

Recent Pages:

·

Lake Mariotis in Ancient Egypt

·

Egyptian hieroglyph and Society

·

Ancient Egypt videos

·

Pan-Grave People and Culture

·

Pepinakht Heqaib

·

Personal Hygiene in Ancient Egypt

·

Perfumes and Unguents in Ancient Egypt